How does the Milky Way compare to other galaxies? We break down the Milky Way vs. Andromeda, ellipticals, and quasars to reveal our galaxy’s true place in the cosmos.

When we look up at the night sky, our Milky Way galaxy feels vast and infinite. This glowing river of light, home to our Sun and billions of other stars, is everything we’ve ever known. But where do we really fit into the grand cosmic zoo? Is our galaxy special, or just one of many?

To answer that, we need to put our home galaxy in a head-to-head lineup with its neighbors and its rivals. We’re going to compare everything: size, shape, power, and even its ultimate fate.

Key Takeaways

After reading this post, you’ll know exactly how the Milky Way stacks up:

- Galaxy Type: The Milky Way is a barred spiral galaxy, a common but beautiful type of galaxy. We live in a flat, rotating disk with massive spiral arms.

- Size: Our galaxy is big, but not the biggest. It’s a major player in our local neighborhood, but it’s dwarfed by “supergiant” galaxies elsewhere in the universe.

- Our Closest Rival: The Andromeda Galaxy (M31) is our nearest large neighbor. It’s visually larger and has more stars, but recent studies suggest the Milky Way might be its equal (or even superior) in total mass, thanks to dark matter.

- Activity: The Milky Way is a “living” galaxy, actively forming new stars at a steady pace. This sets it apart from “dead” elliptical galaxies that ran out of gas billions of years ago.

- Black Hole: Our central supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A*, is a “sleeping giant.” It’s incredibly quiet compared to the blazing, all-powerful black holes known as quasars, which can outshine their entire host galaxies.

- The Future: We are on a collision course with Andromeda. In about 4.5 billion years, our two galaxies will merge in a cosmic dance to form a new, giant elliptical galaxy nicknamed “Milkomeda.

- Location, Location, Location: Perhaps our most defining feature is our address. We live in a quiet “galactic suburb” called the Local Group. This peaceful environment is why our galaxy has preserved its beautiful spiral shape, sparing us the violence of a dense galactic city.

What Exactly Is the Milky Way?

Before we compare our home to others, we need a clear profile of what it is. From the inside, we see it as a luminous, milky band of light, which is actually the edge-on view of a massive, rotating disk. [1]

But this inside view is a challenge. Much of our galaxy is hidden by a fog of interstellar dust, creating a “Zone of Avoidance” that makes mapping our own home incredibly difficult. [3] What we know is a masterpiece of detective work, using infrared and radio telescopes to pierce that veil.

Our Home’s Blueprint: A Barred Spiral Galaxy

The Milky Way is classified as a large barred spiral galaxy, or “SB(rs)bc” for the pros. [1] Let’s break that down:

- Spiral (S): We live in a flattened, spinning disk. This is obvious because we see the “Milky Way” as a concentrated band. If we lived in an elliptical galaxy, stars would be scattered all across the sky. [4]

- Barred (B): Infrared surveys that cut through the dust confirm our galaxy has a large, peanut-shaped bar of stars at its center. [1, 5] This bar acts like a cosmic funnel, channeling gas and stars.

- Spiral Arms: Our disk isn’t uniform. It’s organized into magnificent spiral arms. This is where most of the gas, dust, and young, hot stars are concentrated. Our own Solar System is located in a minor, partial arm called the Orion-Cygnus Spur, about 27,000 light-years from the center. [3, 4]

The Sleeping Giant at Our Core: Sagittarius A*

At the precise gravitational center of our galaxy lies a supermassive black hole (SMBH) named Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*).

We know it’s there because we’ve watched stars whip around it at incredible speeds, orbiting a compact, invisible object with the mass of 4.1 million Suns. [3, 6] In 2022, the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration gave us the final proof: a direct image of the black hole’s shadow. [1]

As we’ll see later, this 4-million-solar-mass black hole is a lightweight compared to some, and it’s currently in a deep slumber.

How Big is the Milky Way? A Galaxy Size Comparison

This seems like a simple question, but it’s one of the most hotly debated topics in astronomy. Size” can mean two different things: the visible disk of stars, or the total mass including the invisible dark matter halo.

Measuring the Milky Way’s Size and Mass

- Visible Size: The Milky Way’s starry disk is traditionally estimated to be about 100,000 light-years across. It’s incredibly thin, only about 1,000 light-years thick. [1] It contains an estimated 100 to 400 billion stars. [3]

- Total Mass (The Great Debate): For decades, the Milky Way’s total mass (including its vast dark matter halo) was thought to be around 1.5 trillion times the mass of the Sun ($1.5 \times 10^{12}\ M_{\odot}$). [3]

But a revolutionary 2023 study using new data from the Gaia space telescope has turned this on its head.

This study found that the galaxy’s mass may be 4 to 5 times less than we thought, at only about 200 billion solar masses ($2.06 \times 10^{11}\ M_{\odot}$). [14] This result is highly controversial and flies in the face of decades of other evidence. [16] This ongoing debate shows just how hard it is to weigh a galaxy from the inside.

The True Giants: Milky Way vs. IC 1101

So, is the Milky Way a big galaxy? Yes. Is it the biggest? Not even close.

For perspective, let’s look at a true behemoth: IC 1101. This is a “supergiant” cD galaxy, the monstrous king of the Abell 2029 galaxy cluster.

- IC 1101: Its diffuse halo of stars extends for 4 million light-years in diameter. [70]

- Milky Way: Our disk is about 100,000 light-years across.

If you placed IC 1101 where our galaxy is, it would physically swallow our entire Local Group, including the Andromeda Galaxy. [71] It’s estimated to contain up to 100 trillion stars, compared to our paltry 100-400 billion. [70]

Galaxies like IC 1101 are a different class of object, built from the cannibalized remains of thousands of other galaxies over cosmic time. Our Milky Way is a “large spiral,” but it’s completely dwarfed by these cosmic emperors.

The Ultimate Rivalry | How Does the Milky Way Compare to Andromeda?

Our most important comparison is with our closest major rival, the Andromeda Galaxy (M31). Located just 2.5 million light-years away, Andromeda is the only other large galaxy in our Local Group and has been our primary benchmark for decades. [27, 29]

Size, Stars, and Mass: Who’s the Big Brother?

For a long time, the answer was simple: Andromeda was the “big brother.”

- Visual Size: Andromeda’s stellar disk is massive, spanning up to 220,000 light-years. This is significantly larger than the Milky Way’s ~100,000 light-year disk. [28]

- Star Count: Andromeda is home to an estimated 1 trillion stars, more than double the high-end estimate for the Milky Way. [28]

Case closed, right? Not so fast. When it comes to total mass (including dark matter), the picture gets fuzzy. Recent studies have revised Andromeda’s mass downward, while other studies have revised the Milky Way’s mass upward (ignoring the 2023 Gaia study for a moment).

The current consensus is that the two galaxies are surprisingly comparable in total mass, both falling in the range of ~1-1.5 trillion solar masses. [28, 33] Despite its smaller visual size, our Milky Way may have a more extensive dark matter halo, making it Andromeda’s equal or even its superior in a gravitational tug-of-war.

Activity Level: Who’s Building More Stars?

This is where the Milky Way currently has a clear lead. A galaxy’s “vitality” is measured by its Star Formation Rate (SFR).

- Milky Way: We are consistently building new stars, converting about 1.65 to 2 solar masses of gas into stars each year. [18] Some recent estimates, using gamma-ray telescopes, suggest this rate could be as high as 4 to 8 solar masses per year. [19]

- Andromeda: M31 is much quieter, with an SFR of only 0.4 to 1 solar mass per year. [18]

Hubble Space Telescope surveys show Andromeda has a more violent past, with major merger events that triggered huge bursts of star formation, followed by long quiet periods. [37] The Milky Way, by contrast, seems to have had a more tranquil history.

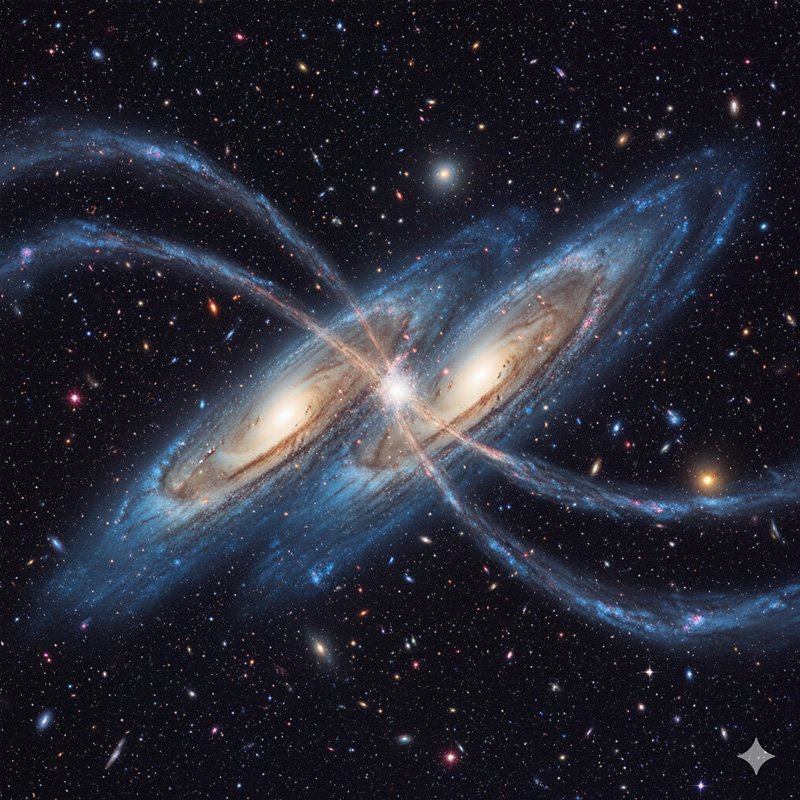

The Inevitable Collision: The Future “Milkomeda”

This cosmic rivalry has a definitive end. Pulled together by their mutual gravity, the Milky Way and Andromeda are hurtling toward each other at 110 km/s (over 245,000 mph). [31]

In about 4.5 billion years, this cosmic collision will begin. [38]

Don’t panic. “Collision” is a misnomer. The distances between stars are so vast that direct star-on-star impacts are negligible. [38] Instead, the two galaxies will pass through each other multiple times, their beautiful spiral structures torn apart by immense tidal forces.

This process will trigger a massive starburst, compressing all their gas and igniting a firestorm of star formation. Over another two billion years, their cores will merge and settle into a single, massive, featureless elliptical galaxy. [38]

This new galaxy has been nicknamed “Milkomeda.” [38] Our Sun will likely survive, but it will be thrown into a new, much larger orbit within this new, giant, and more chaotic home.

How Does the Milky Way Compare to Other Types of Galaxies?

To really understand our galaxy, we need to compare it to the other main classes in the Hubble “tuning fork” diagram: ellipticals and irregulars.

Order vs. Chaos: Milky Way vs. Irregular Galaxies

Irregular galaxies are defined by what they lack: any regular shape. [49] They have no spiral arms and no central bulge.

- Characteristics: They are typically smaller than the Milky Way and are bursting with gas, dust, and bright, young, blue stars. [48, 49]

- Example: Our own satellite galaxies, the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, are classic examples. Their chaotic shapes are the result of the Milky Way’s immense gravity tearing them apart. [43, 47]

The Milky Way is a triumph of order. Its immense mass and angular momentum have organized it into a stable, spinning disk. Irregular galaxies, by contrast, are either too small to get organized or have had their structure violently disrupted by a large neighbor.

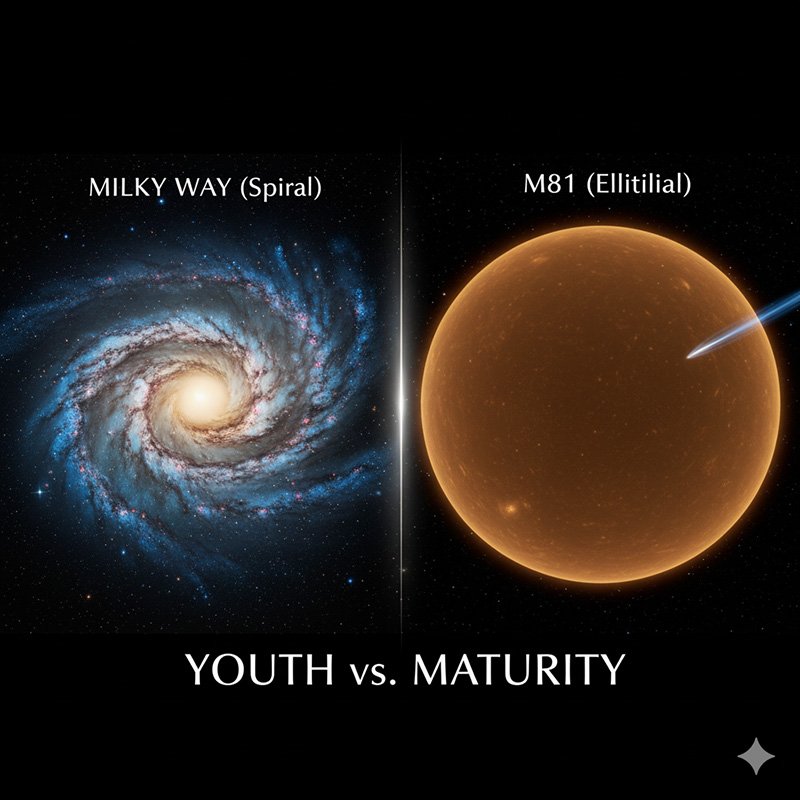

Youth vs. Old Age: Milky Way vs. Elliptical Galaxies

If spiral galaxies like ours are in their active adulthood, elliptical galaxies represent cosmic old age.

- Characteristics: Ellipticals are smooth, featureless, 3D spheres or ovals of stars. [30] They are dominated by old, reddish (Population II) stars.

- Activity: They contain almost no cold gas or dust, meaning the fuel for new star formation ran out billions of years ago. [66] This has earned them the nickname “red and dead” galaxies. [66]

- Example: A prime example is M87, the supergiant elliptical galaxy at the heart of the Virgo Cluster. M87 is a behemoth, hundreds of times more massive than the Milky Way, with a central black hole over 1,000 times more massive than Sgr A*. [68]

The contrast is stark. The Milky Way is a living galaxy, with blue, gas-rich spiral arms acting as stellar nurseries. Elliptical galaxies are settled, quiescent systems—the likely end-state for mergers… just like the one our own galaxy is heading for.

Is the Milky Way an “Active” Galaxy?

A galaxy’s “metabolism” is defined by two engines: making stars and feeding its central black hole. In both categories, the Milky Way is decidedly “middle of the road,” lacking the violent extremes found elsewhere.

What is a Starburst Galaxy?

Our Milky Way’s steady star formation rate is sustainable. Starburst galaxies are not.

- Definition: A starburst galaxy is a galaxy experiencing an exceptionally high rate of star formation, sometimes hundreds or even thousands of times greater than the Milky Way’s. [73]

- Trigger: This is a temporary, violent phase, usually triggered by a galaxy collision or merger. The interaction compresses vast gas clouds, igniting a galaxy-wide firestorm of star birth. [74]

- Example: The classic example is M82, which is forming stars about 10 times faster than our galaxy due to a gravitational run-in with its neighbor, M81. [74]

The Milky Way’s star formation is a calm, steady marathon confined to its spiral arms. A starburst is a brief, unsustainable, all-out sprint.

What is a Quasar? (Sagittarius A* vs. Quasars)

The most extreme comparison involves our central black hole. Sgr A* is a sleeping kitten. Quasars are roaring lions.

Quasars are the most luminous and powerful subclass of Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN). [81] They are, simply put, the brightest objects in the universe.

- Power Source: A quasar is a supermassive black hole that is actively and voraciously feeding on enormous amounts of gas and dust. This material forms a superheated accretion disk that can outshine all 100 billion stars in its host galaxy combined. [80]

- The Stark Contrast:

- Sagittarius A* (Our SMBH): Total power output is less than 2,500 times the luminosity of our Sun. [84]

- Typical Quasar (e.g., 3C 273): Luminosity can exceed 1 trillion solar luminosities ($>10^{12}\ L_{\odot}$). [84] That’s thousands of times brighter than our entire Milky Way galaxy.

This is why Sgr A* is called quiescent, or dormant. [86] It’s “starving,” accreting only a tiny trickle of matter. A quasar is a black hole feasting at a galactic buffet.

Evidence of Our Galaxy’s Rowdier Past

Our galaxy wasn’t always this quiet. There is compelling evidence that Sgr A* was once much more active.

Astronomers have discovered two enormous, invisible structures extending 25,000 light-years above and below the galactic plane. Called the Fermi Bubbles, these lobes glow in gamma rays and X-rays. [87]

They are widely believed to be the “exhaust” or “smoke” from a powerful outburst from Sagittarius A* that happened just a few million years ago. This suggests our galaxy may have gone through its own brief, “mini-quasar” or AGN phase in the relatively recent past. [87]

My Personal “Aha!” Moment on Galactic Scale

As a writer for The Universe Episodes, I read these astronomical numbers all the time. 100,000 light-years,” “400 billion stars,” “4.1 million solar masses.” They’re so massive they become abstract, just words on a page.

My true “aha!” moment—the instant this all became real—happened a few years ago on a camping trip, far from city lights. I pointed my modest telescope at a faint, fuzzy patch of sky I’d located on a star chart.

That patch was the Andromeda Galaxy.

It was faint, just a ghostly smudge of light. But the realization hit me like a ton of bricks: that faint smudge was a trillion stars. It was bigger than my own galaxy. And the light hitting my eye had been traveling for 2.5 million years to reach me. It was a time machine and a measuring stick all in one. Seeing our “rival” with my own eyes, as a physical object in the sky, made the Milky Way’s scale feel suddenly, profoundly tangible.

What is the Milky Way’s “Cosmic Address”?

A galaxy’s evolution is defined by its environment. Its “address” determines its entire life story.

Our Quiet Suburb: The Local Group

The Milky Way is one of the two dominant members of the Local Group, a gravitationally bound collection of over 80 galaxies. [25]

- Structure: The Local Group is a “dumbbell” shape, with the Milky Way and its satellites on one end and the Andromeda Galaxy and its satellites on the other. [25]

- Composition: Besides the two giants (and the smaller spiral, M33), the group is almost entirely composed of small, faint “dwarf” galaxies.

- Environment: This is a low-density, sparse “galactic suburb.” [89] There are no giant elliptical galaxies, and violent, high-speed encounters are rare.

The Outskirts of a Metropolis: The Virgo Supercluster

The Local Group is not an island. It’s an outlying member of a much grander structure: the Virgo Supercluster. [2] This enormous collection contains at least 100 galaxy groups and clusters, spanning over 110 million light-years. [90]

At the heart of this supercluster is the Virgo Cluster, a dense, chaotic “galactic metropolis” of over 1,300 galaxies. [69]

The Virgo Cluster’s core is a violent, destructive environment.

- It’s dominated by giant elliptical galaxies like M87. [92]

- It’s filled with a superheated plasma (ICM). Galaxies flying through this medium at high speed are subjected to “ram pressure stripping”—a cosmic wind that violently blows all their gas and dust away, killing their ability to form new stars. [92]

This comparison highlights the most crucial factor of our galaxy’s identity. The Milky Way could have been a “red and dead” galaxy… if it had been born in a different neighborhood.

Conclusion | The Milky Way’s True Cosmic Identity

So, how does the Milky Way compare to other galaxies?

The Milky Way is a “fortunate representative.”

It is not an extreme. It is not the biggest, the most massive, or the most active galaxy in the universe. Instead, it is a grand and representative example of a mature spiral galaxy.

Its most defining characteristic is its location. By evolving in the quiet, sheltered environment of the Local Group’s suburbs, it has been spared the violent, transformative processes that dominate the dense “cities” like the Virgo Cluster.

This peaceful existence allowed it to maintain its vast, delicate disk of gas and dust. It allowed it to sustain billions of years of orderly star formation. And it allowed it to preserve the magnificent spiral structure we see today.

The Milky Way is not a cosmic anomaly. It is a magnificent, yet not wholly atypical, example of a galaxy in a fortunate phase of its life—providing a precious and relatively stable platform from which life could emerge and begin to comprehend its place in the universe.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Is the Milky Way the biggest galaxy in the universe?

No. The Milky Way is a large spiral galaxy, but it is not the biggest. Our neighbor Andromeda is visually larger, and “supergiant” elliptical galaxies like IC 1101 can be hundreds of times more massive and contain trillions more stars.

Will the Milky Way really collide with Andromeda?

Yes. Based on all current measurements, the two galaxies are on a direct collision course and will begin to merge in about 4.5 billion years. Our solar system will likely survive, but it will be thrown into a new orbit within a new, giant elliptical galaxy.

How many stars are in the Milky Way?

The exact number is impossible to count, but astronomers estimate the Milky Way contains between 100 billion and 400 billion stars.

What is at the center of the Milky Way?

At the very center is a supermassive black hole named Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*). It has a mass of about 4.1 million times that of our Sun and is currently in a “quiescent” or dormant state.

What’s the difference between the Milky Way’s black hole and a quasar?

The difference is activity. A quasar is a supermassive black hole that is actively devouring enormous amounts of matter, causing it to shine thousands of times brighter than its entire galaxy. The Milky Way’s black hole is “dormant,” accreting only a tiny trickle of material, making it extremely faint.