The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will study the Milky Way’s center by combining sensitive near-infrared imaging with an exceptionally wide field of view to penetrate thick interstellar dust and resolve millions of crowded stars. Through the Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey (GBTDS), Roman will monitor this dense region for prolonged periods to detect exoplanets, black holes, and neutron stars using gravitational microlensing and transit methods.

Key Takeaways

- Infrared Penetration: Roman operates in near-infrared wavelengths to see through the dust that blocks optical light from the Galactic Center.

- Wide-Field Monitoring: Its Wide Field Instrument covers large patches of the sky, allowing it to track millions of stars simultaneously in crowded environments.

- Dual Detection Methods: The telescope uses both gravitational microlensing and transit photometry to find planets in wide orbits and rogue planets.

- High Cadence: Roman will observe six specific fields continuously for 72-hour blocks to catch fleeting astronomical events.

Why is the Galactic Center so difficult to observe?

The center of the Milky Way presents three primary obstacles to astronomers: distance, dust, and crowding.

- Distance: The region is approximately 26,000 light-years away. This extreme distance dims the light from stars and events, requiring highly sensitive instruments to detect faint signals.

- Dust Extinction: Thick clouds of interstellar dust lie between Earth and the Galactic Center. This dust absorbs and scatters visible light, rendering the region nearly opaque to standard optical telescopes.

- Crowding: The density of stars in the Galactic Bulge is immense. Stars appear stacked on top of one another, making it difficult to resolve individual objects or measure the brightness of a single star accurately.

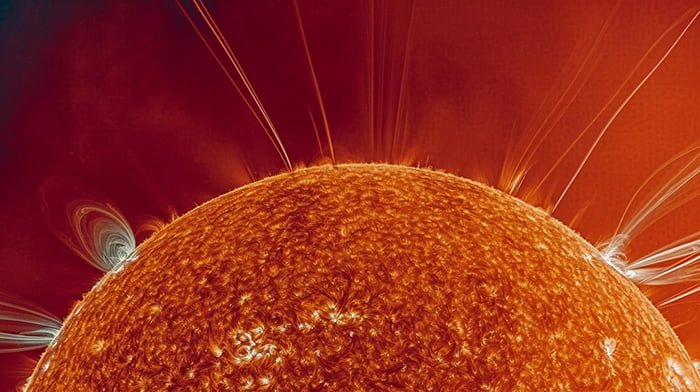

How does the Roman Space Telescope solve the dust problem?

Roman solves the dust problem by observing in the near-infrared spectrum. Unlike visible light, infrared light has longer wavelengths that can pass through dust clouds with significantly less scattering.

This capability allows Roman to see “through” the fog of the Galactic plane. By ignoring the optical wavelengths that get blocked and focusing on infrared, Roman can image the structural details and stellar populations of the bulge that are invisible to optical observatories.

What is the Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey (GBTDS)?

The Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey (GBTDS) is one of Roman’s three core community surveys. It is a long-term monitoring campaign designed to create a census of exoplanets and compact objects in the Milky Way.

The survey is structured around six “seasons” spread over the mission’s first few years. During each season, Roman will monitor six specific fields in the Galactic Bulge. Five of these fields are contiguous and chosen for high star counts with manageable dust, while the sixth field covers the Galactic Center itself, including Sagittarius A*.

How do microlensing and transits work together?

Roman utilizes two complementary methods to detect exoplanets, providing a more complete picture of planetary demographics than previous missions.

Gravitational Microlensing

Microlensing occurs when a massive object (like a star or planet) passes in front of a background star. The gravity of the foreground object bends and magnifies the light of the background star.

- Target: Planets in wide orbits (similar to Jupiter or Saturn) and free-floating “rogue” planets.

- Advantage: Does not require the host star to be bright; can detect planets thousands of light-years away.

Transit Photometry

The transit method detects the slight dip in brightness when a planet crosses directly in front of its host star.

- Target: Planets in close-in, short-period orbits.

- Advantage: Provides statistics on the frequency of Earth-sized planets and allows for future atmospheric studies.

What are the expected discoveries from Roman?

galaxy.” class=”wp-image-23695″/>

galaxy.” class=”wp-image-23695″/>Based on current simulations and mission parameters, astronomers expect Roman to yield a massive dataset of new objects.

| Object Type | Estimated Yield | Scientific Value |

| Microlensing Planets | ~1,000 | Reveals planets in wide orbits and cold regions. |

| Transiting Planets | >100,000 | Provides statistics on planetary frequency in the bulge. |

| Rogue Planets | Statistical sample | Tests theories of planetary formation and ejection. |

| Compact Objects | Thousands | Identifies isolated black holes and neutron stars. |

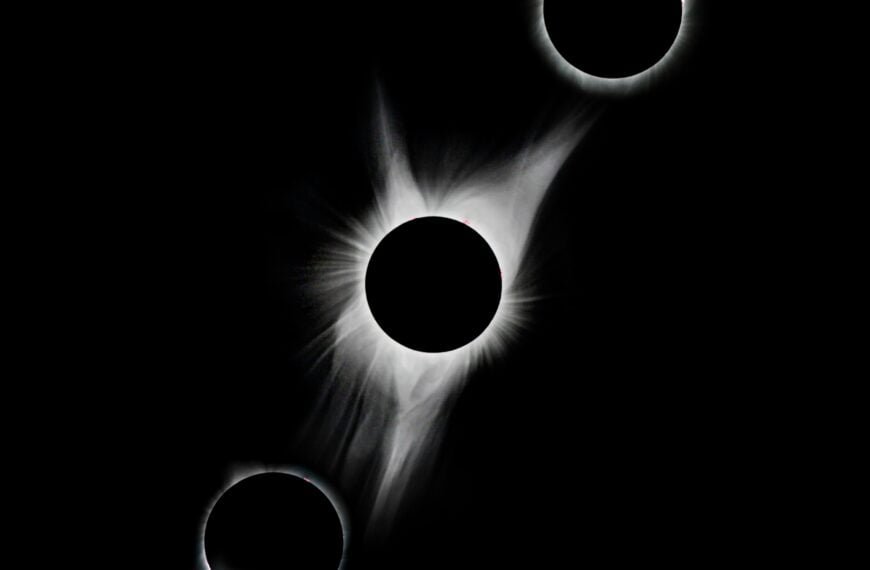

How does Roman compare to Hubble and JWST?

Roman occupies a unique niche compared to other major space telescopes.

- Hubble Space Telescope: Offers high resolution but has a small field of view and is limited primarily to optical and ultraviolet wavelengths, which cannot penetrate deep dust.

- James Webb Space Telescope (JWST): Features powerful infrared sensitivity and resolution but has a narrow field of view. It is designed for deep, pointed observations rather than wide surveys.

- Roman Space Telescope: Combines the resolution of Hubble with a field of view 100 times larger. This makes it the ideal instrument for large-scale surveys of crowded fields.

Expert Insight: Why I Trust Roman for Crowded Fields

This section reflects the technical analysis of astronomical survey strategies.

As someone who has tracked the evolution of survey telescopes, I find the “city square in a fog” analogy best describes the challenge of the Galactic Center. Imagine trying to identify a specific person in a crowd of a million people, through a heavy fog, from miles away.

Ground-based telescopes struggle with the “fog” (atmosphere and dust). Hubble can see clearly but only sees a “keyhole” view. Roman changes the game because it removes the fog (via infrared) and widens the view to see the whole crowd at once.

The most critical feature of the Roman mission plan is the cadence. By staring at the same patch of sky for 72 continuous hours per season, Roman eliminates the day-night gaps that plague ground-based observatories. This continuity is essential for catching the short-lived spikes of a microlensing event or the brief dip of a planetary transit.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

When will the Roman Space Telescope launch?

The Roman Space Telescope is currently scheduled to launch in late 2026 or 2027. It will travel to the Sun-Earth Lagrange Point 2 (L2) for a five-year primary mission.

Yes, indirectly. Roman can detect isolated black holes and neutron stars by measuring how their strong gravity bends light from background stars (microlensing) or by detecting slight shifts in their position (astrometry).

Why is the survey looking at the Galactic Center if it is so dusty?

The Galactic Center is the most star-dense region of our galaxy. Despite the dust, observing this direction provides the highest number of background stars necessary to detect rare microlensing events.

What is the difference between Roman and the Vera Rubin Observatory?

The Vera Rubin Observatory is a ground-based telescope that surveys the sky in optical light. Roman is space-based and surveys in infrared light, allowing it to see through dust and operate 24/7 without atmospheric interference.