Yes. The first detection of thiepine—a 13-atom sulfur-bearing ring molecule—in interstellar space demonstrates that complex prebiotic chemistry happens in molecular clouds before planets even form. This discovery bridges the gap between simple space molecules and the complex organics found in meteorites, suggesting life’s ingredients are manufactured throughout the galaxy, not just on planets.

Key Takeaways

- Thiepine (C₆H₆S) is the largest sulfur-bearing ring molecule ever detected in space, found 27,000 light-years away near the Galactic center

- The molecule was confirmed using laboratory spectroscopy matched against radio telescope observations from two independent facilities in Spain

- This discovery links interstellar chemistry directly to meteorite organics, supporting the idea that planets inherit prebiotic molecules from space rather than creating them from scratch

- Sulfur is essential to Earth biology (found in proteins and enzymes), making sulfur-bearing space molecules particularly relevant to life’s origins

- The detection occurred in a molecular cloud that exists before star formation, meaning complex chemistry begins earlier in the cosmic timeline than previously confirmed

What exactly is thiepine and why does it matter?

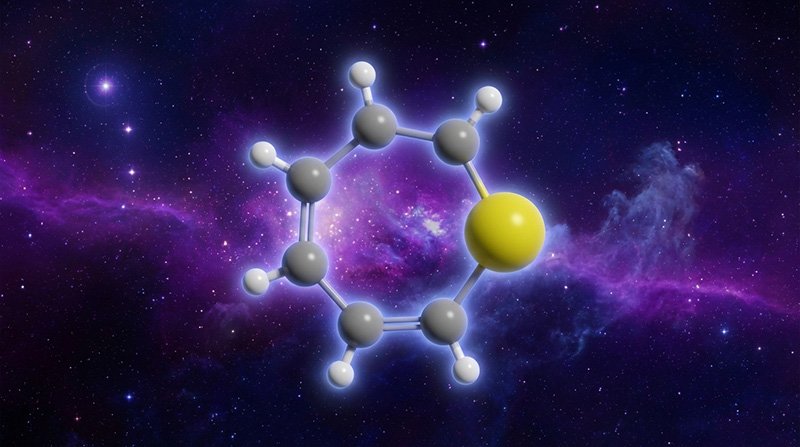

Thiepine is a ring-shaped organic molecule containing six carbon atoms, six hydrogen atoms, and one sulfur atom arranged in a stable six-membered ring structure. It matters because sulfur plays critical roles in Earth biology—it’s a core component of amino acids like cysteine and methionine, and it’s essential for protein structure and enzyme function.

Before this discovery, astronomers had only detected small sulfur molecules in space (like H₂S and CS, typically six atoms or fewer). Thiepine represents a significant jump in complexity with 13 total atoms and a stable ring structure that resembles organic compounds found in carbonaceous meteorites.

The molecule acts as a chemical bridge: it’s more complex than previously confirmed interstellar molecules but simpler than the organic materials we see in meteorite samples. This makes it a crucial missing link in understanding how complex chemistry develops in space.

How did scientists confirm this molecule in space?

The confirmation required a two-step process combining laboratory chemistry with radio astronomy.

Laboratory synthesis and measurement:

- Scientists at the Max Planck Institute synthesized thiepine by applying a 1,000-volt electrical discharge to thiophenol (a related sulfur-bearing compound)

- They used a custom spectrometer to measure thiepine’s unique radio-frequency “fingerprint”—the specific wavelengths it emits when rotating in space

- This created a reference library of spectral lines to search for in astronomical data

Telescope observations:

- The IRAM 30-meter and Yebes 40-meter radio telescopes in Spain scanned the molecular cloud G+0.693–0.027

- Astronomers matched multiple emission lines from the cloud to the laboratory-measured thiepine signature

- Finding several matching lines (not just one) across different frequencies eliminated the risk of misidentification in the crowded spectral environment

This multi-line match across independent telescopes and laboratory data provides what researchers call “unambiguous” detection—the gold standard in astrochemistry.

Where in space was thiepine found?

Thiepine was detected in the molecular cloud G+0.693–0.027, located approximately 27,000 light-years from Earth near the center of the Milky Way galaxy.

This cloud is particularly important because:

- It’s a dense, chemically rich environment that has produced numerous molecular discoveries

- The region experiences shocks and energetic processing (from cosmic rays and turbulence) that drive complex chemistry

- It represents the type of cold, dense cloud that gives birth to new stars and planetary systems

- It’s a pre-stellar environment, meaning complex molecules form before stars ignite and planets begin to coalesce

The cloud’s proximity to the Galactic center makes it chemically active but also creates challenges for observation due to crowded spectral lines from hundreds of other molecules.

How does thiepine form in space?

Scientists propose several plausible formation pathways, and likely more than one operates simultaneously:

Grain-surface chemistry: Molecules form on icy coatings that cover dust grains in the cloud. When cosmic rays or ultraviolet light hit these grains, they trigger radical chemistry that can build rings and incorporate sulfur atoms. Shock waves or heating can then release these molecules into the gas phase where telescopes detect them.

Energetic processing: The laboratory method—using electrical discharge on thiophenol—simulates high-energy processes like cosmic-ray bombardment. This suggests that similar energetic events in space could convert simpler sulfur compounds into thiepine.

Gas-phase radical reactions: In regions with elevated density and temperature (caused by shocks), reactive molecular fragments can collide and combine to build larger structures including rings.

The electrical discharge experiment is particularly revealing because it demonstrates a direct transformation from a plausible precursor molecule to thiepine, giving credibility to the idea that this chemistry occurs naturally in energetic space environments.

What sulfur molecules were known before this discovery?

Previous sulfur detections in space included only small, simple molecules:

| Molecule | Formula | Atom count |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon monosulfide | CS | 2 |

| Hydrogen sulfide | H₂S | 3 |

| Sulfur dioxide | SO₂ | 3 |

| Carbonyl sulfide | OCS | 3 |

| Thioformaldehyde | H₂CS | 4 |

Thiepine (C₆H₆S) with 13 atoms represents more than double the size of these previously detected sulfur-bearing molecules. Its ring structure also adds stability and chemical complexity not present in the simpler linear or three-atom molecules previously known.

This size jump is significant—it demonstrates that interstellar chemistry can produce organics approaching the complexity of molecules found in returned comet samples and meteorites.

Why does this discovery matter for understanding life’s origins?

This detection strengthens three key ideas about how life’s chemical ingredients become available:

1. Prebiotic inventory arrives from space: Planets don’t start with blank slates. They inherit a molecular toolkit from the clouds and disks that form them. Finding complex sulfur organics in pre-stellar clouds means this toolkit is richer than previously confirmed.

2. Meteorite chemistry has interstellar origins: Meteorites contain complex sulfur-bearing organics structurally similar to thiepine. This detection narrows the gap between what we see in space and what arrives on planetary surfaces, suggesting continuity from cloud to planet rather than separate chemistry on each body.

3. Complex chemistry begins before planets exist: Because thiepine was found in a molecular cloud that predates star formation, the chemical groundwork for life starts earlier in the cosmic timeline than planetary chemistry alone would suggest. This implies prebiotic chemistry is a galactic-scale phenomenon, not just a planetary one.

The discovery doesn’t prove life exists elsewhere, but it does make the universe look substantially richer in potentially useful prebiotic molecules than conservative estimates suggested.

Does this molecule directly lead to life?

No. Thiepine itself is not a building block of life in the direct sense that amino acids or nucleotides are.

However, it’s part of a broader chemical inventory that matters for two reasons:

- Sulfur availability: Life on Earth depends on sulfur for protein structure, enzyme catalysis, and electron transfer. Finding sulfur already incorporated into complex organic structures in space means it’s available in forms that could participate in further prebiotic chemistry on planets.

- Chemical diversity: The presence of stable ring structures with heteroatoms (non-carbon atoms like sulfur in rings) demonstrates that interstellar chemistry can produce the kinds of molecular scaffolds seen in biology, even if the specific molecules differ.

Think of it as evidence that the chemical “language” of biology—diverse organics with rings, functional groups, and heteroatoms—is written in space long before life emerges.

What should I expect from follow-up research?

The scientific community will pursue several immediate directions:

Searches in other locations: Astronomers will look for thiepine in other molecular clouds, protoplanetary disks around young stars, and comet observations to determine if it’s common or unique to shock-processed regions like G+0.693–0.027.

High-resolution mapping: Interferometers like ALMA can map exactly where in the cloud thiepine concentrates—on grain surfaces, in shock fronts, or in dense cores—revealing formation conditions.

Laboratory spectroscopy expansion: Measuring spectral signatures of related sulfur-bearing rings will allow identification of additional complex molecules and distinguish between structural isomers (molecules with the same formula but different arrangements).

Chemical modeling: Theorists will refine models of grain-surface and gas-phase chemistry to reproduce thiepine abundances and predict which other molecules should form under similar conditions.

Meteorite and comet comparisons: Direct comparison between thiepine and organics extracted from meteorite samples or measured in cometary comae will test whether the same molecules survive incorporation into small bodies and delivery to planets.

| Follow-up activity | What it reveals |

|---|---|

| Surveys of other clouds | How common thiepine is galaxy-wide |

| ALMA/NOEMA mapping | Where and how the molecule forms |

| Lab work on isomers | Which related molecules exist but haven’t been identified yet |

| Reaction modeling | Which formation pathways are most efficient |

| Meteorite comparison | Whether the same molecules reach planets |

What are the limitations of this discovery?

I want to be clear about what this finding does not establish:

- It’s a single detection in one cloud: Until thiepine is found in multiple locations, we can’t conclude it’s ubiquitous

- Survival through planet formation is uncertain: Harsh conditions during disk collapse and planet assembly may destroy complex molecules

- Abundance matters but isn’t yet detailed: Initial reports emphasize detection over quantifying how much thiepine exists relative to other molecules

- Spectral crowding risks: The Galactic center has thousands of molecular lines; while multi-line matching reduces error, some ambiguity remains until more observations occur

These limitations don’t diminish the importance of the detection—they simply define the work still needed to fully understand what it means.

My perspective as someone who follows astrochemistry

I’ve been tracking interstellar organic chemistry for years, and this detection feels like a genuine step change rather than an incremental addition to the molecular census.

What strikes me most is how it reframes the timeline of prebiotic chemistry. I used to think of planetary surfaces as the primary factories for complex organics—warm pools, hydrothermal vents, atmosphere chemistry. This discovery and others like it push that chemistry backward in time to cold molecular clouds that exist millions of years before planets.

The combination of rigorous laboratory work and multi-telescope confirmation also reassures me about the detection’s robustness. Astrochemistry faces constant challenges with spectral confusion and instrumental artifacts. Seeing multiple independent lines of evidence converge makes this one of the more convincing complex-molecule announcements in recent years.

I don’t interpret this as proof that life is common, but it does make me more confident that the raw ingredients for prebiotic chemistry are widespread. If thiepine can form in the harsh, low-density environment of interstellar space, then the galaxy produces a richer chemical palette than I would have guessed two decades ago.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the largest molecule ever found in space?

The largest confirmed molecule in interstellar space is fullerene C₆₀ (buckminsterfullerene), a cage-like structure with 60 carbon atoms. Thiepine is the largest sulfur-bearing ring molecule detected, with 13 atoms total. Size records in astrochemistry depend on molecular class—fullerenes, chains, and rings each have different complexity champions.

Can thiepine survive on a planet’s surface?

Likely not in its pure form for long. Thiepine would react with other molecules, decompose under UV light, or transform in the presence of water and minerals. However, its presence in space suggests it or related molecules could be incorporated into planetesimals, comets, and asteroids, where some fraction may survive delivery to planetary surfaces during impacts.

How common is sulfur in space?

Sulfur is the tenth most abundant element in the universe, but much of it appears “missing” in molecular clouds—it’s not seen in expected quantities in the gas phase. Scientists think sulfur is locked up in ices on dust grains or in refractory minerals. Finding complex sulfur organics like thiepine helps solve part of this “missing sulfur” problem by showing where some of it hides chemically.

Are ring molecules more important than chain molecules for life?

Not necessarily more important, but they offer different chemical properties. Rings are often more stable and can create rigidity in larger structures (like the rings in DNA nucleotides). Chains offer flexibility. Life on Earth uses both extensively. Finding rings in space shows that interstellar chemistry produces both types, expanding the toolkit available to planets.

Could this molecule be a sign of life itself?

No. Thiepine can form through non-biological chemistry, as demonstrated by the laboratory synthesis using electrical discharge. It’s a potential ingredient for life, not a biosignature. Biosignatures require molecules or patterns that are extremely unlikely to form without biology, typically involving thermodynamic disequilibrium or highly specific structural complexity.