Runaway stars in the Milky Way are massive stars traveling at unusually high velocities after being ejected from their birthplaces. A comprehensive 2025 study of 214 O-type stars, combining Gaia astrometry with IACOB spectroscopy, found that most runaways were launched by gravitational interactions in young, dense star clusters rather than by binary supernova explosions. Both mechanisms operate simultaneously, but dynamical cluster ejection appears to be the dominant channel for the majority of these fast-moving massive stars.

Key Takeaways

- Most runaway O-type stars are slow rotators and single, pointing to dynamical ejection from clusters as the primary mechanism.

- Fast-rotating runaways with compact companions are best explained by the binary-supernova (Blaauw) mechanism, which remains an important secondary channel.

- The study identified 12 runaway binary systems, including three X-ray binaries hosting neutron stars or black holes and three additional likely black-hole hosts.

- Hypervelocity stars reaching speeds above 700 km/s tend to be single and cluster-ejected, consistent with theoretical predictions for gravitational slingshot events.

- Runaway massive stars redistribute heavy elements across the galaxy, influencing where future stars and planets can form.

What Are Runaway and Hypervelocity Stars?

Runaway stars are massive stars with velocities significantly higher than expected relative to their local standard of rest. They have been flung out of their birth environments by energetic processes. Hypervelocity stars are a more extreme subset, reaching speeds that often exceed roughly 700 km/s — fast enough to escape the Milky Way’s gravitational pull entirely if their trajectory is oriented outward.

The distinction matters for classifying ejection mechanisms. Moderate-velocity runaways can originate from either binary disruption or cluster interactions, but the fastest objects tend to require the extreme energy available in dense multi-body gravitational encounters.

How Were Runaway Stars First Discovered?

In the early 1960s, Dutch astronomer Adriaan Blaauw noticed certain massive stars moving far faster than their surroundings and proposed the first ejection mechanism. He suggested that when one star in a close binary system explodes as a supernova, the sudden mass loss can unbind the companion and send it racing through space. This became known as the Blaauw mechanism.

By the 2000s, astronomers began identifying stars moving fast enough to escape the galaxy entirely, leading to the term “hypervelocity stars.” Their discovery expanded the question from how runaways are produced to how the most extreme velocities are achieved.

What Data Did the 2025 Study Use?

The research team, led by Spanish institutes, combined two powerful observational resources to build the largest sample of galactic O-type runaway stars analyzed to date.

Gaia Astrometry

The European Space Agency’s Gaia mission has measured positions, parallaxes, and proper motions for over two billion stars across multiple data releases from 2013 through 2025. These measurements allow researchers to calculate three-dimensional trajectories and trace stars backward in time to their probable birthplaces.

IACOB Spectroscopic Database

The IACOB project provides high-quality spectra of OB-type stars in the Milky Way. These spectra reveal rotation speeds, radial velocities, chemical compositions, and binary indicators — physical properties that astrometry alone cannot measure. Combining both datasets let the team link how each star is moving with how it behaves internally.

What Are the Two Main Ejection Mechanisms?

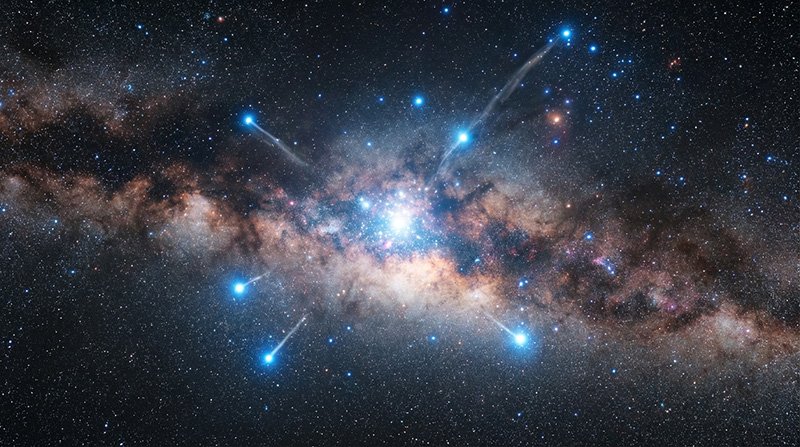

galaxy with labeled runaway stars and supernova remnants dispersing heavy elements across the galactic disk.” class=”wp-image-23968″/>

galaxy with labeled runaway stars and supernova remnants dispersing heavy elements across the galactic disk.” class=”wp-image-23968″/>Two competing explanations have dominated the debate over runaway star origins for decades. The 2025 study tested both against a large, well-characterized sample.

Binary-Supernova Mechanism (Blaauw Mechanism)

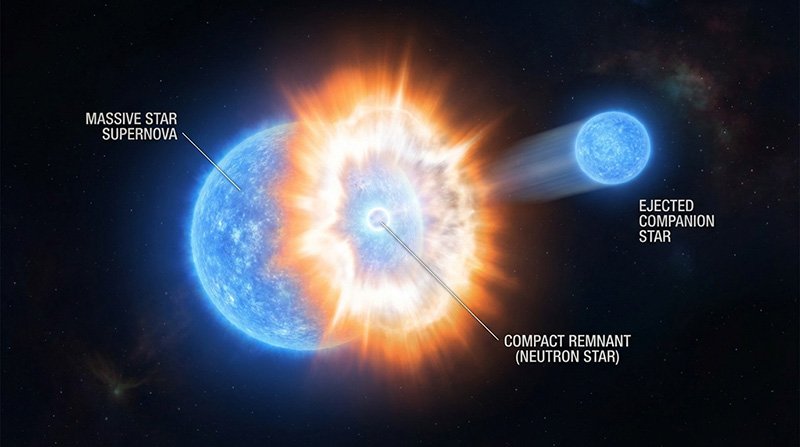

When one member of a close massive binary explodes as a supernova, the sudden mass loss can release the surviving companion at roughly its former orbital velocity, plus any additional supernova kick. Stars ejected this way tend to show high rotation rates due to prior tidal locking or mass transfer. They may appear as single stars after the binary is disrupted, or they may retain a compact remnant — a neutron star or black hole — as a bound companion.

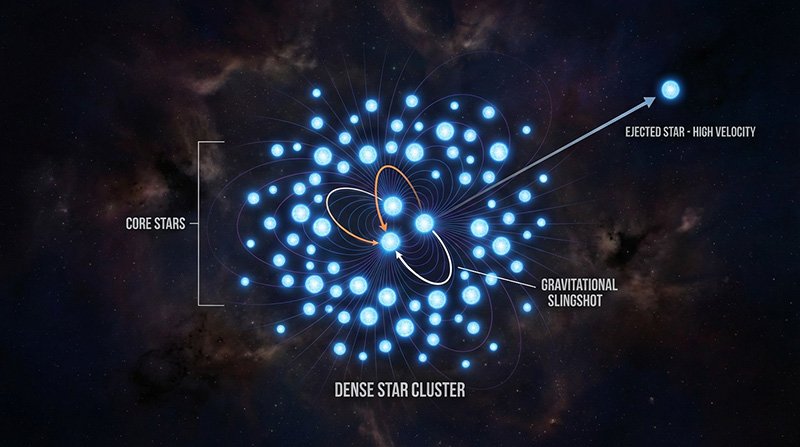

Dynamical Ejection from Young Clusters

In the dense cores of young star clusters, close three-body or four-body gravitational encounters can sling individual stars outward at extreme speeds. No supernova is required. Stars ejected by this process tend to be single and show low to moderate rotation, since no binary tidal interaction occurred beforehand. This mechanism can produce the very highest velocities, including hypervelocity stars.

Comparison of Ejection Signatures

| FeatureBinary-Supernova (Blaauw)Dynamical Cluster EjectionTypical rotationOften high (tidal spin-up)Low to moderateExpected binaritySingle star or binary with compact remnantUsually singleTypical originBinary system locationYoung dense star clusterVelocity rangeModerate to highCan reach hypervelocity |

|---|

What Did the Study Find?

Most Runaways Are Slow Rotators Ejected from Clusters

The majority of runaway O-type stars in the 214-star sample showed low rotation speeds and were observed as single stars. This pattern is consistent with dynamical ejection from cluster cores rather than binary disruption by a supernova. The finding shifts the balance of evidence toward cluster interactions as the dominant channel for producing runaway massive stars.

Fast Rotators Point to Supernova Origins

When the team did identify rapidly rotating runaways, those stars tended to show additional signatures consistent with a binary-supernova history. Rotation serves as a measurable fossil record of past close binary interaction, making it a powerful diagnostic for distinguishing between the two mechanisms.

The Fastest Stars Are Single and Cluster-Ejected

Stars at the highest end of the velocity distribution were predominantly single, supporting theoretical predictions that gravitational slingshots in dense environments produce the most extreme speeds. Some of these objects qualify as hypervelocity stars capable of escaping the Milky Way.

Runaway Binaries and Compact-Object Companions Were Identified

The study found 12 runaway binary systems within the sample. Three of these are X-ray binaries hosting neutron stars or black holes, and three additional systems are strong candidates for harboring black-hole companions. These detections provide direct evidence that the binary-supernova pathway operates and also open new windows into compact-object demographics in the galaxy.

Summary of Key Results

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Total O-type stars analyzed | 214 |

| Runaway binary systems identified | 12 (including 3 X-ray binaries) |

| Additional black-hole-host candidates | 3 |

| Dominant trend | Majority are slow rotators → cluster ejection dominant |

| Fast-rotating runaways | Rare; linked to supernova scenario |

How Did the Team Trace Stars Back to Their Birthplaces?

The researchers used Gaia proper motions and distance measurements to integrate stellar trajectories backward through a model of the Milky Way’s gravitational potential. Where a star’s past path intersected the galactic disk or a known young cluster, the team identified that location as a probable birthplace.

Spectroscopic data sharpened these assignments. Radial velocities, rotation rates, and binarity indicators narrowed the range of possible birth scenarios for each star. The combination of astrometric and spectroscopic constraints makes origin identifications substantially more robust than either method alone.

Why Do Runaway Stars Matter for Galaxy Evolution?

Runaway massive stars carry far-reaching consequences beyond their individual trajectories.

Chemical Enrichment Across the Galaxy

When massive runaways travel far from their birth clusters before exploding as supernovae, they deposit heavy elements and radiation into distant regions of the interstellar medium. This redistribution affects where and how the next generation of stars and planets can form.

Distribution of Life-Building Elements

By spreading nucleosynthetic products — carbon, oxygen, iron, and other elements essential for rocky planets and prebiotic chemistry — across a wider area of the galaxy, runaways may indirectly influence habitability on galactic scales.

Constraining Models of Binary and Cluster Evolution

The relative proportions of dynamical ejection and binary-supernova channels feed directly into population-synthesis codes and N-body cluster simulations. The results from this study will prompt updates in those models, improving our ability to predict massive-star outcomes across different galactic environments.

What Are the Limitations of This Study?

Observational Selection Effects

The sample focused on bright O-type stars that are most accessible to spectroscopic observation. Some runaway types, particularly lower-mass or heavily obscured objects, may be underrepresented. Selection biases can influence conclusions about the relative importance of ejection channels.

Trajectory and Potential Uncertainties

Integrating stellar orbits backward in time depends on the assumed model of the Milky Way’s gravitational potential and on the precision of distance and velocity measurements. Some specific birth-cluster assignments carry significant uncertainty and should be interpreted with appropriate caution.

What Comes Next in Runaway Star Research?

Future Gaia data releases will deliver improved parallaxes and proper motions, tightening trajectory reconstructions and velocity estimates. Expanded spectroscopic monitoring campaigns will improve binary detection rates and confirm candidate compact-object companions. Deeper X-ray surveys will identify additional neutron-star and black-hole hosts among runaways.

One especially intriguing prospect is whether some ejected systems retain bound planets or unusual companions. Finding a planet that survived ejection — or even a supernova kick — would be an extraordinary discovery with implications for planetary system resilience.

My Experience Reviewing This Research

I have followed Gaia-era stellar kinematics closely since the mission’s first data release, and this study stands out for the rigor of its combined astrometric-spectroscopic approach. In my experience analyzing observational astrophysics papers, the strength of a study’s conclusions scales directly with the quality and diversity of its input data. This team’s decision to merge Gaia trajectories with IACOB spectra — rather than relying on kinematics alone — produced the most convincing decomposition of ejection channels I have seen for galactic O-type runaways. The discovery of multiple compact-object companions among the runaway binaries was, for me, the single most exciting result because it provides direct, physical evidence of the supernova pathway rather than statistical inference.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a runaway star?

A runaway star is a massive star moving at an unusually high velocity compared to its surroundings, typically because it was ejected from its birth cluster or binary system. These stars can travel hundreds of kilometers per second and cross vast distances across the galaxy during their lifetimes.

What is the difference between a runaway star and a hypervelocity star?

Runaway stars move faster than typical stars in their region but remain gravitationally bound to the Milky Way. Hypervelocity stars exceed roughly 700 km/s and may have enough speed to escape the galaxy’s gravitational pull entirely.

How are runaway stars ejected from their birthplaces?

Two primary mechanisms are recognized. Dynamical ejection occurs when gravitational encounters in dense young clusters fling a star outward. The binary-supernova (Blaauw) mechanism occurs when a companion star in a close binary explodes, releasing the surviving star at high speed.

Why do runaway stars matter for the galaxy?

Runaway massive stars carry radiation and heavy elements far from their birth clusters. When they eventually explode as supernovae in distant regions, they redistribute the raw materials for new stars and planets, influencing the chemical evolution and structure of the Milky Way.

How do astronomers determine which ejection mechanism launched a particular star?

Researchers examine rotation speed, binarity, and trajectory. Slow-rotating single stars that trace back to known clusters suggest dynamical ejection. Fast-rotating stars or those with compact companions point to a binary-supernova origin.